In case you’ve been waiting for an update, I apologize for the delay! Let’s dive into the numbers.

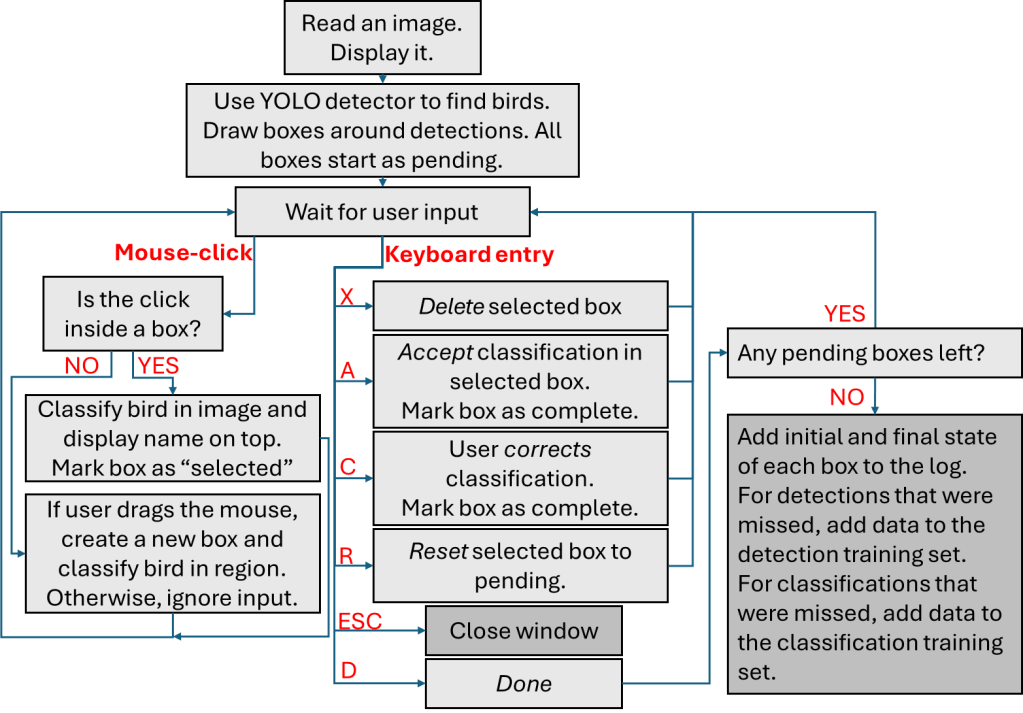

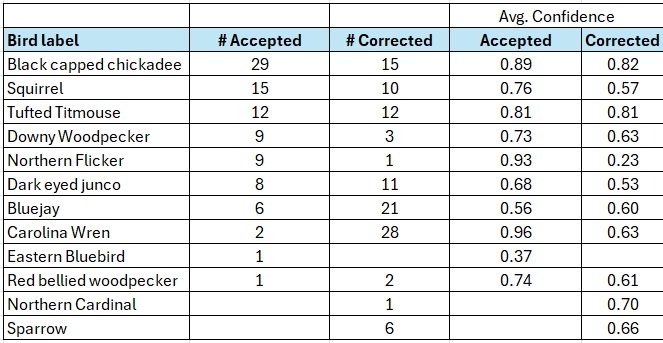

At the time of writing, I’ve used my custom detection and classification pipeline to go through 115 images, identifying 202 birds (a category which now includes squirrels 😅). Of these, 45% were correctly detected. There were 25 false detections – these were often multiple boxes for the same bird or boxes that only partially selected the bird. I accepted 92 classifications, which is also about 45%.

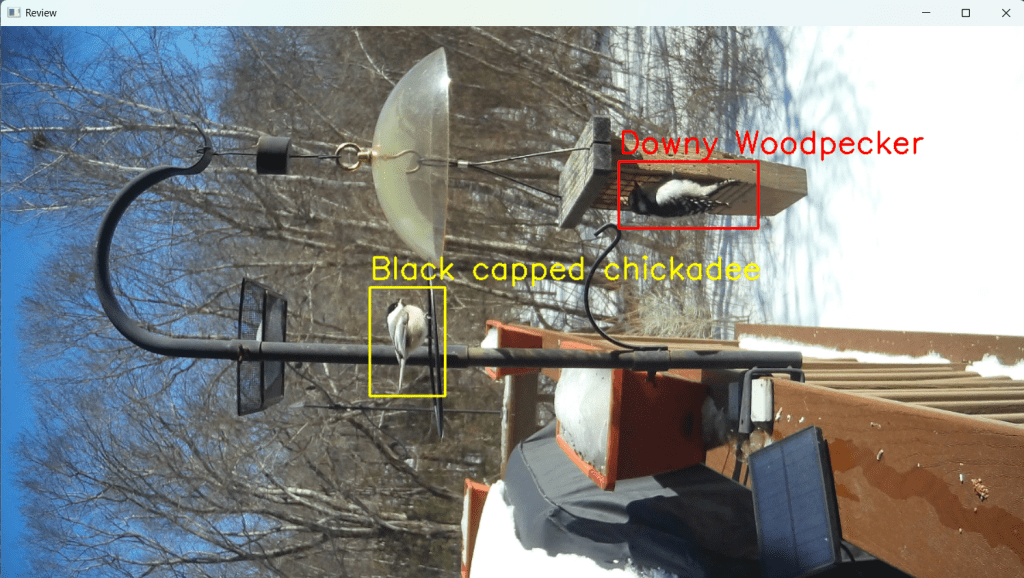

I’m especially happy with how well it identified Black-capped chickadees, Downy woodpeckers, Northern flickers and squirrels (to be fair they are pretty distinct). On the flip side, in the messy space of “small brown birds” the model struggles just as much as I do.

The obvious next step is to use refine both detection and classification models with the new training data. I might also add the ability to distinguish between male and female birds – especially when they look significantly different from each other, such as Northern Cardinals, Downy woodpeckers and House Finches. It would be a good time to experiment with different starting models to see how they perform. Does one need less training data, or is one faster to train or more accurate?

I had created a table that showed me how often different birds appeared each month – but it was heavily skewed by how often I pulled images from the camera and which birdfood was on offer. Perhaps first and last observation dates for migratory birds might be more useful, or identifying times of day when certain birds are more active than others.

For now, I’m calling this phase of the project complete. I learned a bunch about machine-learning and “vibe-coding” and also accomplished my original goal of reducing the time I spend sorting through trail camera images.

If you have feedback, or ideas for where to take this next, or want to set up something similar – I’d love to hear from you.

For now, I’ll leave you with some of my favorite captures.

Previous post: Custom detection and classification